For more than 75 years, most of us learned that our solar system had nine planets. We memorized their names, and Pluto was always the last one on the list: the small, icy world at the edge. But in 2006, scientists made a big announcement that changed our textbooks. They decided Pluto was no longer a planet. This news was surprising and even a little sad for many people. It felt like a favorite character was being written out of the story.

This decision was not made lightly. It was not a sudden choice to just “demote” Pluto. Instead, it was the result of many years of new, exciting discoveries. These discoveries completely changed our understanding of the outer solar system. Scientists found new objects and new regions of space they never knew existed. This forced them to stop and ask a very important question: what truly makes a planet a planet?

The story of Pluto is not really about a demotion. It is a story about how science works. As we get better tools, like more powerful telescopes, we learn new things. Sometimes, that new information forces us to update our old definitions and see the universe in a new way. So, what exactly did we discover that made Pluto lose its famous title?

The hunt for Pluto began long before it was ever seen. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, astronomers were studying the orbits of the two most distant known planets, Uranus and Neptune. They noticed that Neptune’s orbit seemed to have tiny, unexplained wobbles. One astronomer, Percival Lowell, was convinced that the gravity of another, unseen planet was pulling on it. He called this mysterious object “Planet X.” Lowell built an entire observatory in Arizona to find it, but he died before his search was successful.

The search for Planet X continued at the Lowell Observatory. In 1929, the job was given to a 23-year-old astronomer from Kansas named Clyde Tombaugh. His job was incredibly difficult. He had to take thousands of photographs of the night sky. He would take a picture of one small patch of stars, and then take another picture of the same patch a few nights later. He then used a machine called a “blink comparator” to flip back and forth between the two images. He was looking for one tiny dot of light that had moved against the background of fixed stars.

On February 18, 1930, after almost a year of this tiring work, Tombaugh saw it. A tiny dot had jumped. He had found Planet X. The discovery was a worldwide sensation. The observatory received over a thousand letters suggesting names. The winning name, “Pluto,” was suggested by an 11-year-old girl from England named Venetia Burney. She thought the dark, distant world should be named after the Roman god of the underworld. It was a perfect fit, and Pluto officially became our solar system’s ninth planet.

For decades, Pluto’s status as the ninth planet was accepted without much question. It was the only object known to exist beyond the orbit of Neptune. It was a dot of light, and it circled the Sun, so it had to be a planet. Textbooks, models of the solar system, and encyclopedias all included it. Culturally, Pluto became a beloved part of our cosmic family. It was the smallest, the farthest, and the most mysterious.

During this time, our knowledge about it was very limited. From Earth, even with the best telescopes, Pluto was just a faint, blurry speck. Astronomers were able to figure out its 248-year orbit and its distance, but not much else. Its identity as a “planet” was based more on the fact that it was the only thing we had found out there. There was no other category for it to fit into.

The “Planet X” theory also helped. Because astronomers expected to find a planet, they treated Pluto like one when they found it. Even though they soon realized Pluto was far too small to cause the wobbles in Neptune’s orbit (which, it turned in, were just measurement errors), the “planet” label stuck. For over 75 years, Pluto was a full-fledged member of the club, and there was no strong reason to challenge it. That is, until our technology finally got good enough to see what else was hiding in the darkness.

Even when it was considered a full planet, astronomers knew Pluto was strange. It did not really fit in with the other planets in either of the two main groups. The first four planets, like Earth and Mars, are small, rocky worlds. The next four, like Jupiter and Saturn, are giant balls of gas and ice. Pluto was in its own category. It was a tiny ball of ice and rock, smaller than Earth’s own Moon.

Its orbit was another big clue. The eight main planets orbit the Sun on a flat, level plane, almost like marbles rolling on a dinner plate. But Pluto’s orbit is different. It is tilted at a steep 17-degree angle, so it travels far above and below that flat plane. Its path is also very stretched out, like a long oval. For 20 years of its 248-year journey, Pluto’s orbit actually crosses inside the orbit of Neptune. This means that from 1979 to 1999, Neptune was actually the farthest planet from the Sun, not Pluto.

The final strange clue came in 1978 with the discovery of Pluto’s moon, Charon. This moon was a huge discovery because it was not small at all. Charon is about half the size of Pluto itself. Because it is so large, Charon does not orbit Pluto in the normal way. Instead, Pluto and Charon orbit a point in space between them, like two dancers spinning each other around while holding hands. This is called a binary system. None of the other planets have a moon anywhere near that large in proportion to themselves. All these clues—its tiny size, its weird tilted orbit, and its giant moon—suggested Pluto was something different.

The real challenge to Pluto’s status began in 1992. Astronomers started finding other objects orbiting the Sun out in the same distant region as Pluto. The first one was a small body called 1992 QB1. Soon, they were finding hundreds, and then thousands, of these icy objects. They realized that Pluto was not alone in the dark. It was just the first and largest member of a massive, newly discovered “third zone” of the solar system.

This zone is called the Kuiper Belt. Think of it as a giant, icy junkyard that lies beyond Neptune. It is filled with trillions of leftover building blocks from when the solar system was formed. It is like the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter, but much, much bigger and made of ice instead of rock. Pluto is just the king of the Kuiper Belt. This discovery put scientists in a tough spot. If Pluto was a planet, did that mean all these new objects were planets, too?

We have actually seen this problem before in history. In the 1800s, astronomers discovered an object named Ceres in the gap between Mars and Jupiter. They called it a planet. But then they found another object, Pallas, and called it a planet. Then Juno, then Vesta. They soon realized they were finding dozens of objects in that same orbit. They were not planets; they were part of a giant “Asteroid Belt.” Ceres was then reclassified as the largest asteroid. History was now repeating itself. Pluto was just the first “Ceres” of this new, icy “Kuiper Belt.”

The “Pluto problem” came to a crisis point in 2005. An astronomer named Dr. Mike Brown and his team, who had been scanning the skies for years, made a huge announcement. They had discovered a new object, far beyond Pluto, in the outer edges of the Kuiper Belt. They nicknamed it “Xena” at first, but it was later given the official name Eris, after the Greek goddess of discord and strife. The name was perfect, because Eris caused a lot of trouble.

The trouble was this: after careful measurements, the team confirmed that Eris was more massive than Pluto. It was heavier and, at the time, thought to be larger. This was a breaking point for astronomy. The public and the scientific community had to face a simple question. If Pluto is Planet 9, then Eris must be Planet 10. But what about the other large objects the same team had found, like Makemake and Haumea? They were also big, almost as big as Pluto.

Astronomers realized they were on the verge of opening a floodgate. They might soon have a solar system with 20, 50, or even 100 planets. The word “planet” would become cluttered and lose its meaning. It would be impossible for anyone to remember them all. The discovery of Eris, a world bigger than Pluto, was the final push. It proved that Pluto was not unique. It was time for scientists to officially define the word “planet” for the very first time.

In August 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) met in Prague for a big conference. The IAU is the official group of astronomers from around the world that is in charge of naming objects in space. One of their biggest tasks at this meeting was to settle the planet debate once and for all. After much discussion, they voted on and passed the first official scientific definition of a planet.

According to the IAU, for a celestial body to be considered a “planet,” it must meet three conditions. These three rules are now the standard used by astronomers.

- It must orbit the Sun. It cannot be a moon orbiting another planet.

- It must have enough mass for its own gravity to pull it into a round shape (or nearly round). This is called hydrostatic equilibrium. Lumpy, potato-shaped asteroids do not count.

- It must have “cleared its neighborhood” of other objects.

When they applied these three rules, the results were clear. The first eight worlds—Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—all passed. Pluto, however, did not. It passed the first two rules easily. It orbits the Sun, and it is definitely round. But it failed, and failed badly, on rule number three.

This third rule is the most important one, and it is also the most confusing. “Clearing the neighborhood” does not mean the planet’s orbit is perfectly empty. Earth, for example, has asteroids that cross its path. What it really means is that the planet has become the gravitationally dominant object in its orbit.

Think of it this way: a true planet is the “boss” of its orbital zone. As it formed over billions of years, its powerful gravity did one of three things to all the other “stuff” (like asteroids and debris) in its path. It either:

- Pulled the stuff in and “ate” it (like impacts that made the planet grow);

- Captured the stuff and turned it into a moon; or

- Used its gravity to fling the stuff away into deep space.

The result is that a real planet, like Earth or Jupiter, has a mass that is thousands of times greater than all the other debris in its orbital path combined. Earth is the boss.

Now, let’s look at Pluto. Pluto is not the boss of its orbit. It is a resident in a very crowded neighborhood, the Kuiper Belt. It is surrounded by millions of other icy objects, rocks, and comets. If you added up the mass of all that other stuff in Pluto’s orbital zone, you would find it is far greater than the mass of Pluto itself. Pluto is not the dominant object. It is just one large object among many. It has not “cleared” its path. This is the single, scientific reason why Pluto is no longer called a main planet.

This reclassification was not meant as an insult to Pluto. Scientists needed a new category for this new type of world they had discovered. So, the IAU created a brand new classification: the dwarf planet.

A dwarf planet is an object that meets the first two rules of the planet definition, but fails the third.

- It orbits the Sun (Rule 1: Check).

- It is round (Rule 2: Check).

- It has not cleared its neighborhood (Rule 3: Fail).

This was a perfect solution. It acknowledges that Pluto is not just a random rock. It is a complex, round world with its own geology and moons. It is a “planet-like” object. But it also separates it from the main eight planets, which are in a class of their own due to their gravitational dominance.

Pluto was the first object to be named a dwarf planet, but it was not the only one. Eris, the object that started the whole debate, was also classified as a dwarf planet. So were Ceres (the largest object in the Asteroid Belt) and the other large Kuiper Belt objects, Makemake and Haumea. Pluto was not “demoted” to a lower rank; it was “promoted” to be the most famous member of a whole new and exciting family of worlds.

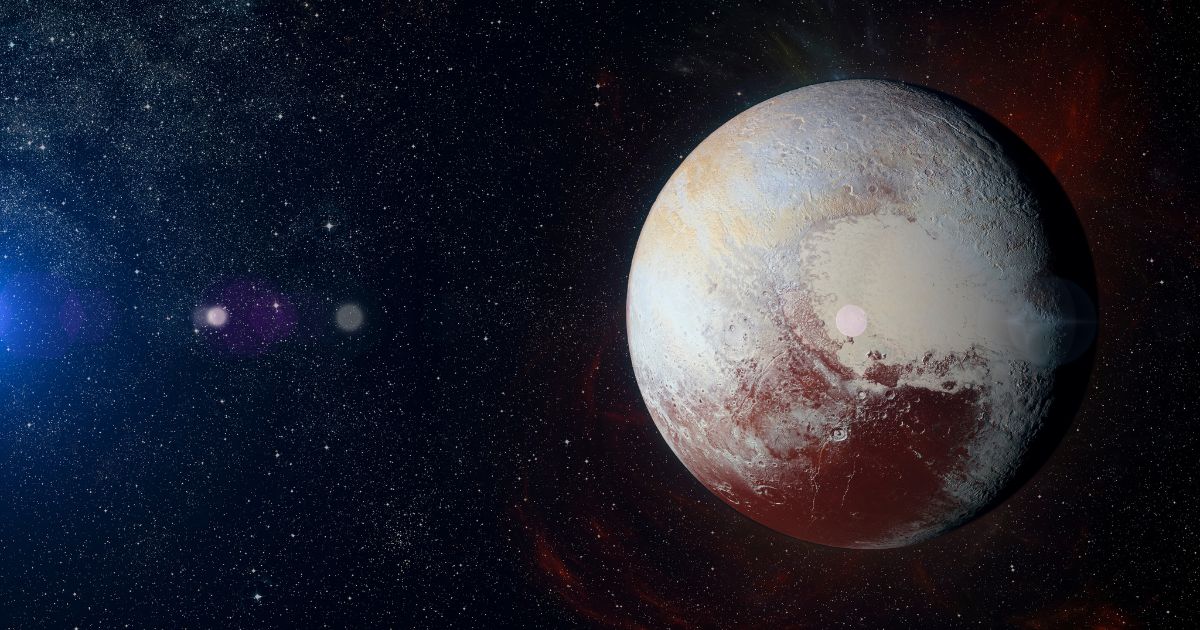

For all of history, Pluto was just a blurry dot. But on July 14, 2015, everything changed. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, which had traveled for nine and a half years and over three billion miles, finally flew past Pluto. The images it sent back to Earth were absolutely breathtaking. They shocked everyone.

Pluto was not a dead, boring, cratered ice ball. It was a stunningly complex and geologically active world. The most famous feature is a giant, heart-shaped plain of frozen nitrogen, named Tombaugh Regio after its discoverer. This “heart” is smooth and has almost no craters, meaning its surface is young. It is a vast, slowly churning glacier of exotic ices. This activity means Pluto must have a source of internal heat, possibly from a liquid water ocean sloshing deep beneath its icy shell.

The spacecraft also found towering mountains made of solid water ice, some as tall as the Rocky Mountains on Earth. It found a hazy blue atmosphere, five different moons, and deep canyons. The New Horizons flyby proved that “dwarf planet” does not mean “uninteresting.” In fact, Pluto has become one of the most fascinating and mysterious objects in our entire solar system. It showed us that these small, distant worlds are just as complex and beautiful as the main planets.

Officially, the debate is settled. The IAU is the governing body, and its definition of eight planets and a growing list of dwarf planets is the standard used in astronomy textbooks and by the scientific community. When NASA talks about the solar system, it lists eight planets. This is the formal, accepted model. However, the discussion is not completely over, which is normal and healthy for science.

Some scientists, particularly planetary scientists who study geology, are not happy with the 2006 IAU definition. They prefer a different definition based on an object’s physical properties, not its location. This is often called the geophysical definition. To them, a “planet” is any object in space that is round due to its own gravity. By this definition, Pluto is a planet. But this definition would also make Eris, Ceres, and even Earth’s Moon planets. This would give us over 100 planets in our solar system.

The debate is really about two different ways of thinking. The IAU definition is dynamic; it cares about what an object does in its orbit. The geophysical definition is geological; it cares about what an object is (its shape and body). For now, the IAU’s three-rule definition is the official one. But the fact that scientists are still debating shows that our solar system is more complex and wonderful than we ever imagined.

The story of Pluto is not a sad one. It is a story of discovery. For 75 years, we thought Pluto was a lonely, tiny planet at the edge of a simple solar system. But new technology revealed the truth: Pluto is not alone at all. It is the king of a huge, crowded, and exciting new region of space called the Kuiper Belt, filled with thousands of other icy worlds.

Because of these new discoveries, like Eris, scientists had to create a new definition for “planet.” This new definition requires a planet to be the gravitational boss of its own orbit, a test that the eight main planets pass but Pluto does not. Pluto was reclassified as a “dwarf planet,” a new category for round, complex worlds that share their orbital paths with many other objects.

Then, when the New Horizons mission showed us Pluto’s heart, its ice mountains, and its blue sky, it proved that a label does not make a world special. Pluto is a dynamic and beautiful world, no matter what we call it. It is a reminder that the solar system is bigger, stranger, and more wonderful than we ever knew. Does it really matter what we call an object, as long as we continue to explore it?

Pluto stopped being called a main planet because of new discoveries. Scientists found that Pluto is not alone in its orbit. It is part of a huge new region called the Kuiper Belt, which is full of thousands of other icy objects.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) made the official decision in 2006. The IAU is the group of astronomers from all over the world that is in charge of naming and classifying objects in space.

The third rule is that a planet must have “cleared its neighborhood.” This means it must be the gravitationally dominant object in its own orbit, having either absorbed, captured, or thrown away all other large debris.

If Pluto were still considered a planet, then we would also have to call Eris, Makemake, Haumea, and Ceres planets. This is because they are also round and orbit the Sun. We would likely have over 100 planets in our solar system by now.

It is very unlikely. The official 2006 definition from the IAU is widely accepted by the astronomical community. While some scientists still debate the definition, the formal classification of eight planets and many dwarf planets is the standard.

When Eris was first discovered, it was measured to be more massive (heavier) than Pluto. For a long time, it was also thought to be physically larger. However, the New Horizons mission gave us a precise measurement of Pluto, and we now know Pluto is slightly larger in diameter, but Eris is still more massive.

A dwarf planet is a round object that orbits the Sun but has not cleared its orbital neighborhood. It shares its orbit with many other objects. Pluto, Eris, and Ceres are all dwarf planets.

As of 2025, the IAU officially recognizes five dwarf planets: Ceres, Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake. However, scientists believe there may be hundreds, or even thousands, more waiting to be discovered and confirmed in the Kuiper Belt and beyond.

No, the New Horizons mission did not change Pluto’s official classification. It proved that Pluto is a very complex and active world, with mountains, glaciers, and an atmosphere. It showed that “dwarf planets” can be just as interesting as “planets.”

A single year on Pluto, which is one full orbit around the Sun, takes about 248 Earth years. This means that since it was discovered in 1930, Pluto has not even completed half of one full orbit.